Magadha

Kingdom of Magadha | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700 BCE – 28 BCE | |||||||||||||

Kingdom of Magadha and other Mahajanapadas during the second urbanization | |||||||||||||

Territorial expansion of the Magadha empire 6th century BCE onwards | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Rajagriha (Girivraj) Later, Pataliputra (modern-day Patna) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit[1] Magadhi Prakrit Ardhamagadhi Prakrit | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Buddhism Jainism | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Māgadhī | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy[a] | ||||||||||||

| King/Emperor | |||||||||||||

• c. 544 – c. 492 BCE | Bimbisara | ||||||||||||

• c. 492 – c. 460 BCE | Ajatashatru | ||||||||||||

• c. 413 – c. 395 BCE | Shishunaga | ||||||||||||

• c. 395 – c. 367 BCE | Kalashoka | ||||||||||||

• c. 345 – c. 329 BCE | Mahapadma Nanda | ||||||||||||

• c. 329 – c. 321 BCE | Dhana Nanda | ||||||||||||

• c. 321 – c. 297 BCE | Chandragupta Maurya | ||||||||||||

• c. 320 – c. 273 BCE | Bindusara | ||||||||||||

• c. 268 – c. 232 BCE | Ashoka | ||||||||||||

• c. 185 – c. 149 BCE | Pushyamitra Shunga | ||||||||||||

• c. 319 – c. 335 CE | Chandragupta I | ||||||||||||

• c. 335 – c. 375 CE | Samudragupta | ||||||||||||

• c. 375 – c. 415 CE | Chandragupta II | ||||||||||||

• c. 455 – c. 467 CE | Skandagupta | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Panas | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||||||

| Battles / wars | |||||||||||||

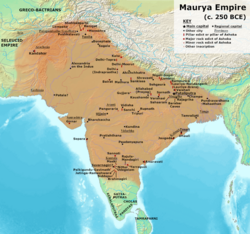

Magadha, also called the Kingdom of Magadha or the Magadha Empire, was a kingdom and empire, and one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas, 'Great Footholds of the People' during the Second Urbanization period, based in southern Bihar in the eastern Ganges Plain, in Ancient India. Magadha was ruled by the Brihadratha dynasty (1700–682 BCE), the Haryanka dynasty (544–413 BCE), the Shaishunaga dynasty (413–345 BCE), the Nanda dynasty (345–322 BCE), the Maurya dynasty (322–184 BCE), the Shunga dynasty (184–73 BCE), the Kanva dynasty (73–28 BCE), the Gupta dynasty (240-550 CE) and the Later Gupta dynasty (490–700). Kanva dynasty lost much of its territory after being defeated by the Satavahanas of Deccan in 28 BCE and was reduced to a small principality around Pataliputra.[2][3] However, with the rule of Gupta Empire (240–550 CE), The Gupta Empire regained the Glory of Magadh. Under the Mauryas, Magadha became a pan-Indian empire, covering large swaths of the Indian subcontinent and Afghanistan. The Magadh under the Gupta Empire emerged as the most prosperous kingdom in the history of Ancient India.

Magadha played an important role in the development of Jainism and Buddhism.[4] It was the core of four of northern India's greatest empires, the Nanda Empire (c. 345 – c. 322 BCE), Maurya Empire (c. 322–185 BCE), Shunga Empire (c. 185–78 BCE) and Gupta Empire (c. 240–550 CE). The Pala Empire also ruled over Magadha and maintained a royal camp in Pataliputra.[5][6]

The Pithipatis of Bodh Gaya referred to themselves as Magadhādipati and ruled in parts of Magadha until the 13th century.[7]

Geography

[edit]

The territory of the Magadha kingdom proper before its expansion was bounded to the north, west, and east respectively by the Gaṅgā, Son, and Campā rivers, and the eastern spurs of the Vindhya mountains formed its southern border. The territory of the initial Magadha kingdom thus corresponded to the modern-day Patna and Gaya districts of the Indian state of Bihar.[8]

The region of Greater Magadha also included neighbouring regions in the eastern Gangetic plains and had a distinct culture and belief. Much of the Second Urbanisation took place here from (c. 500 BCE) onwards and it was here that Jainism and Buddhism arose.[9][failed verification]

History

[edit]

Some scholars have identified the Kīkaṭa tribe—mentioned in the Rigveda (3.53.14) with their ruler Pramaganda—as the forefathers of Magadhas because Kikata is used as synonym for Magadha in the later texts;[10] Like the Magadhas in the Atharvaveda, the Rigveda speaks of the Kikatas as a hostile tribe, living on the borders of Brahmanical India, who did not perform Vedic rituals.[11]

The earliest reference to the Magadha people occurs in the Atharvaveda, where they are found listed along with the Angas, Gandharis and Mujavats. The core of the kingdom was the area of Bihar south of the Ganges; its first capital was Rajagriha (modern day Rajgir), then Pataliputra (modern Patna). Rajagriha was initially known as 'Girivrijja' and later came to be known as so during the reign of Ajatashatru. Magadha expanded to include most of Bihar and Bengal with the conquest of Vajjika League and Anga, respectively.[12] The kingdom of Magadha eventually came to encompass Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, West Bengal, eastern Uttar Pradesh, and the areas that are today the nations of Bangladesh and Nepal.[13]

The ancient kingdom of Magadha is heavily mentioned in Jain and Buddhist texts. It is also mentioned in the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas.

There is little certain information available on the early rulers of Magadha. The most important sources are the Buddhist Pāli Canon, the Jain Agamas and the Hindu Puranas. Based on these sources, it appears that Magadha was ruled by the Haryanka dynasty for some 200 years, c. 543 to 413 BCE.[14]

Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, lived much of his life in the kingdom of Magadha. He attained enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath and the first Buddhist council was held in Rajgriha.[15]

The Hindu Mahabharata calls Brihadratha the first ruler of Magadha. Ripunjaya, last king of Brihadratha dynasty, was killed by his minister Pulika, who established his son Pradyota as the new king. Pradyota dynasty was succeeded by Haryanka dynasty founded by Bimbisara. Bimbisara led an active and expansive policy, conquering the kingdom of Anga in what is now West Bengal. King Bimbisara was killed by his son, Ajatashatru. Pasenadi, king of neighbouring Kosala and brother-in-law of Bimbisara, promptly reconquered the Kashi province.

Accounts differ slightly as to the cause of King Ajatashatru's war with the Licchavi, a powerful tribe north of the river Ganges. It appears that Ajatashatru sent a minister to the area who worked for three years to undermine the unity of the Licchavis. To launch his attack across the Ganges River, Ajatashatru built a fort at the town of Pataliputra. Torn by disagreements, the Licchavis fought with Ajatashatru. It took fifteen years for Ajatashatru to defeat them. Jain texts tell how Ajatashatru used two new weapons: a catapult, and a covered chariot with swinging mace that has been compared to a modern tank. Pataliputra began to grow as a centre of commerce and became the capital of Magadha after Ajatashatru's death.

The Haryanka dynasty was overthrown by the Shishunaga dynasty. The last Shishunaga ruler, Mahanandin, was assassinated by Mahapadma Nanda in 345 BCE, the first of the so-called "Nine Nandas", i. e. Mahapadma and his eight sons, last being Dhana Nanda.

In 326 BCE, the army of Alexander approached the western boundaries of Magadha. The army, exhausted and frightened at the prospect of facing another giant Indian army at the Ganges, mutinied at the Hyphasis (the modern Beas River) and refused to march further east. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer Coenus, was persuaded that it was better to return and turned south, conquering his way down the Indus to the Ocean.

Around 321 BCE, the Nanda Dynasty ended with the defeat of Dhana Nanda at the hands of Chandragupta Maurya who became the first king of the Mauryan Empire with the help of his mentor Chanakya. The Empire later extended over most of India under King Ashoka The Great, who was at first known as 'Ashoka the Cruel' but later became a disciple of Buddhism and became known as 'Dharma Ashoka'.[16][17] Later, the Mauryan Empire ended, as did the Shunga and Khārabēḷa empires, to be replaced by the Gupta Empire. The capital of the Gupta Empire remained Pataliputra in Magadha.

During the Pala-period in Magadha from the 11th to 13th century CE, a local Buddhist dynasty known as the Pithipatis of Bodh Gaya ruled as tributaries to Pala Empire.[7]

Buddhism and Jainism

[edit]Several Śramaṇic movements had existed before the 6th century BCE, and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy.[18] The Śramaṇa movement gave rise to diverse range of heterodox beliefs, ranging from accepting or denying the concept of soul, atomism, antinomian ethics, materialism, atheism, agnosticism, fatalism to free will, idealization of extreme asceticism to that of family life, strict ahimsa (non-violence) and vegetarianism to the permissibility of violence and meat-eating.[19] Magadha kingdom was the nerve centre of this revolution.

Jainism was revived and re-established after Mahavira, the last and the 24th Tirthankara, who synthesised and revived the philosophies and promulgations of the ancient Śramaṇic traditions laid down by the first Jain tirthankara Rishabhanatha millions of years ago.[20] Buddha founded Buddhism which received royal patronage in the kingdom.

According to Indologist Johannes Bronkhorst, the culture of Magadha was in fundamental ways different from the Vedic kingdoms of the Indo-Aryans. According to Bronkhorst, the śramana culture arose in "Greater Magadha," which was Indo-Aryan, but not Vedic. In this culture, Kshatriyas were placed higher than Brahmins, and it rejected Vedic authority and rituals.[9][22] He argues for a cultural area termed "Greater Magadha", defined as roughly the geographical area in which the Buddha and Mahavira lived and taught.[9] [23]

With regard to the Buddha, this area stretched by and large from Śrāvastī, the capital of Kosala, in the north-west to Rājagṛha, the capital of Magadha, in the south-east".[24] According to Bronkhorst "there was indeed a culture of Greater Magadha which remained recognizably distinct from Vedic culture until the time of the grammarian Patañjali (ca. 150 BCE) and beyond".[25] The Buddhologist Alexander Wynne writes that there is an "overwhelming amount of evidence" to suggest that this rival culture to the Vedic Aryans dominated the eastern Gangetic plain during the early Buddhist period. Orthodox Vedic Brahmins were, therefore, a minority in Magadha during this early period.[26]

The Magadhan religions are termed the sramana traditions and include Jainism, Buddhism and Ājīvika. Buddhism and Jainism were the religions promoted by the early Magadhan kings, such as Srenika, Bimbisara and Ajatashatru, and the Nanda Dynasty (345–321 BCE) that followed was mostly Jain. These Sramana religions did not worship the Vedic deities, practised some form of asceticism and meditation (jhana) and tended to construct round burial mounds (called stupas in Buddhism).[25] These religions also sought some type of liberation from the cyclic rounds of rebirth and karmic retribution through spiritual knowledge.

Religious sites in Magadha

[edit]

Among the Buddhist sites currently found in the Magadha region include two UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as the Mahabodhi temple at Bodh Gaya[27] and the Nalanda monastery.[28] The Mahabodhi temple is one of the most important places of pilgrimage in the Buddhist world and is said to mark the site where the Buddha attained enlightenment.[29]

Language

[edit]Beginning in the Theravada commentaries, the Pali language has been identified with Magahi, the language of the kingdom of Magadha, and this was taken to also be the language that the Buddha used during his life. In the 19th century, the British Orientalist Robert Caesar Childers argued that the true or geographical name of the Pali language was Magadhi Prakrit, and that because pāḷi means "line, row, series", the early Buddhists extended the meaning of the term to mean "a series of books", so pāḷibhāsā means "language of the texts".[30] Nonetheless, Pali does retain some eastern features that have been referred to as Māgadhisms.[31]

Magadhi Prakrit was one of the three dramatic prakrits to emerge following the decline of Sanskrit. It was spoken in Magadha and neighbouring regions and later evolved into modern eastern Indo-Aryan languages like Magahi, Maithili and Bhojpuri.[32]

Dynasties and rulers

[edit]The history of Magadha region is very vast, it can be divided into many periods as:

- Vedic Magadha Kingdom :- Kikata kingdom, Brihadratha dynasty

- Magadha Mahajanapada :- Pradyota dynasty, Haryanka dynasty, Shaishunaga dynasty

- Magadha Empire :- Nanda Empire, Maurya Empire, Shunga Empire, Kanva dynasty

- Classical Magadha :- Gupta Empire, Later Gupta dynasty

- Medieval Magadha :- Pala Empire, Pithipatis of Bodh Gaya

There is much uncertainty about the succession of kings and the precise chronology of Magadha prior to Mahapadma Nanda; the accounts of various ancient texts (all of which were written many centuries later than the era in question) contradict each other on many points.

Two notable rulers of Magadha were Bimbisara (also known as Shrenika) and his son Ajatashatru (also known as Kunika), who are mentioned in Buddhist and Jain literature as contemporaries of the Buddha and Mahavira. Later, the throne of Magadha was usurped by Mahapadma Nanda, the founder of the Nanda Dynasty (c. 345 – c. 322 BCE), which conquered much of north India. The Nanda dynasty was overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire (c. 322–185 BCE).

Furthermore, there is a "Long Chronology" and a contrasting "Short Chronology" preferred by some scholars, an issue that is inextricably linked to the uncertain chronology of the Buddha and Mahavira.[33] According to historian K. T. S. Sarao, a proponent of the Short Chronology wherein the Buddha's lifespan was c.477–397 BCE, it can be estimated that Bimbisara was reigning c.457–405 BCE, and Ajatashatru was reigning c.405–373 BCE.[34] According to historian John Keay, a proponent of the "Long Chronology," Bimbisara must have been reigning in the late 5th century BCE,[35] and Ajatashatru in the early 4th century BCE.[36] Keay states that there is great uncertainty about the royal succession after Ajatashatru's death, probably because there was a period of "court intrigues and murders," during which "evidently the throne changed hands frequently, perhaps with more than one incumbent claiming to occupy it at the same time" until Mahapadma Nanda was able to secure the throne.[36]

List of rulers

[edit]The following "Long Chronology" is according to the Buddhist Mahavamsa:[37]

- Haryanka dynasty (c. 544 – 413 BCE)

| Ruler | Reign (BCE) |

|---|---|

| Bimbisara | 544–491 BCE |

| Ajatashatru | 491–461 BCE |

| Udayin | 461–428 BCE |

| Anirudha | 428–419 BCE |

| Munda | 419–417 BCE |

| Darshaka | 417–415 BCE |

| Nāgadāsaka | 415–413 BCE |

- Shishunaga dynasty (c. 413 – 345 BCE)

| Ruler | Reign (BCE) |

|---|---|

| Shishunaga | 413–395 BCE |

| Kalashoka | 395–377 BCE |

| Kshemadharman | 377–365 BCE |

| Kshatraujas | 365–355 BCE |

| Nandivardhana | 355–349 BCE |

| Mahanandin | 349–345 BCE |

- Nanda Empire (c. 345 – c. 322 BCE)

| Ruler | Reign (BCE) |

|---|---|

| Mahapadma Nanda | 345–340 BCE |

| Pandhukananda | 340–339 BCE |

| Panghupatinanda | 339–338 BCE |

| Bhutapalananda | 338–337 BCE |

| Rashtrapalananada | 337–336 BCE |

| Govishanakananda | 336–335 BCE |

| Dashasidkhakananda | 335–334 BCE |

| Kaivartananda | 334–333 BCE |

| Karvinathanand | 333–330 BCE |

| Dhana Nanda | 330–322 BCE |

Other lists

[edit]The Hindu Literature mostly Puranas give a different sequence:[38]

- Shishunaga dynasty (360 years)

- Shishunaga (reigned for 40 years)

- Kakavarna (36 years)

- Kshemadharman (20 years)

- Kshatraujas (29 years)

- Bimbisara (28 years)

- Ajatashatru (25 years)

- Darbhaka or Darshaka or Harshaka (25 years)

- Udayin (33 years)

- Nandivardhana (42 years)

- Mahanandin (43 years)

- Nanda dynasty (100 years)

- List by Jain literature

A shorter list appears in the Jain tradition, which simply lists Shrenika (Bimbisara), Kunika (Ajatashatru), Udayin, followed by the Nanda dynasty.[38]

Historical figures from Magadha

[edit]

Important people from the region of Magadha include:

- Śāriputra – born to a wealthy Brahmin in a village located near Rājagaha in Magadha. He is considered the first of the Buddha's two chief male disciples, together with Maudgalyāyana.[39]

- Maudgalyāyana – born in the village of Kolita in Magadha. He was one of the Buddha's two main disciples. In his youth, he was a spiritual wanderer before meeting the Buddha.[40]

- Mahavira – the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism. Born into a royal kshatriya family in what is now Vaishali district of Bihar. He abandoned all worldly possessions at the age of 30 and became an ascetic. He is considered a slightly older contemporary of the Buddha.[41]

- Maitripada – an 11th-century Indian Buddhist Mahasiddha associated with the Mahāmudrā transmission. Born in the village of Jhatakarani in Magadha. Also associated with the monasteries of Nalanda and Vikramashila.[42]

- Dhyānabhadra - 13th/14th century monk of Nalanda born to a minor chief in Magadha and later travelled across South and East Asia.[43]

- Subhūticandra - 11/12th-century Indian Buddhist monk associated with Nalanda and Vikramashila who belonged to Magadha.[44]

See also

[edit]- Mahajanapadas

- History of India

- Magadha-Vajji war

- Magadha-Anga war

- Avanti-Magadhan Wars

- List of Indian monarchs

- Timeline of Indian history

- Magahi Culture

- Magahi Languages

Notes

[edit]- ^ as described in the Arthashastra

References

[edit]- ^ Jain, Dhanesh (2007). "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan languages". In George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 47–66, 51. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ^ Keny, Liladhar (1943). ""THE SUPPOSED IDENTIFICATION OF UDAYANA OF KAUŚĀMBI WITH UDAYIN OF MAGADHA"". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 24 (1/2): 60–66. JSTOR 41784405.

- ^ Roy, Daya (1986). "SOME ASPECTS OF THE RELATION BETWEEN ANGA AND MAGADHA (600 B.C.—323 B.C.)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 47: 108–112. JSTOR 44141530.

- ^ Damien Keown (26 August 2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. OUP Oxford. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- ^ Jhunu Bagchi (1993). The History and Culture of the Pālas of Bengal and Bihar, Cir. 750 A.D.-cir. 1200 A.D. Abhinav Publications. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-7017-301-4.

- ^ Jha, Tushar; Tyagi, Satish (2017). "CONTOURS OF THE POLITICAL LEGITIMATION STRATEGY OF THE RULERS OF PALA DYNASTY IN BENGAL- BIHAR (CE 730 TO CE 1165)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 78: 49–58.

- ^ a b Balogh, Daniel (2021). Pithipati Puzzles: Custodians of the Diamond Throne. British Museum Research Publications. pp. 40–58. ISBN 9780861592289.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1953). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta. pp. 110–118.

- ^ a b c Bronkhorst 2007, p. [page needed].

- ^ Macdonell, Arthur Anthony; Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1995). Vedic Index of Names and Subjects. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 9788120813328.

- ^ M. Witzel. "Rigvedic history: poets, chieftains, and polities," in The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity. ed. G. Erdosy (Walter de Gruyer, 1995), p. 333

- ^ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0436-8.

- ^ Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha, Cir. 450–1200 A.D. Abhinav Publications. p. 128.

- ^ Chandra, Jnan (1958). "Some Unknown Facts About Bimbisāra". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 21: 215–217. JSTOR 44145194.

- ^ "Lumbini Development Trust: Restoring the Lumbini Garden". Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Tenzin Tharpa, Tibetan Buddhist Essentials: A Study Guide for the 21st Century: Volume 1: Introduction, Origin, and Adaptation, p.31

- ^ Sanjeev Sanyal (2016), The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History, section "Ashoka, the not so great"

- ^ Ray, Reginald (1999). Buddhist Saints in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 237–240, 247–249. ISBN 978-0195134834.

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2001). Collected papers on Buddhist Studies. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 57–77. ISBN 978-8120817760.

- ^ Patel, Haresh (2009). Thoughts from the Cosmic Field in the Life of a Thinking Insect [A Latter-Day Saint]. Strategic Book Publishing. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-60693-846-1.

- ^ "Auction 396. INDIA, Mauryan Empire , Karshapana (14mm, 3.32 g). circa 315-310 BC". www.cngcoins.com. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Long, Jeffery D. (2009). Jainism : an introduction. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-4416-3839-7. OCLC 608555139.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (1997). "Macrocosm, Mesocosm, and Microcosm: The Persistent Nature of 'Hindu' Beliefs and Symbolic Forms". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 1 (3): 501–539. doi:10.1007/s11407-997-0021-x. JSTOR 20106493. S2CID 144673508.

- ^ Bronkhorst 2007, pp. xi, 4.

- ^ a b Bronkhorst 2007, p. 265.

- ^ Wynne, Alexander (2011). "Review of Bronkhorst, Johannes, Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India". H-Buddhism. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ K.T.S. Sarao (16 September 2020). The History of Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya. Springer Nature. pp. 66–. ISBN 9789811580673.

- ^ Pintu Kumar (7 May 2018). Buddhist Learning in South Asia: Education, Religion, and Culture at the Ancient Sri Nalanda Mahavihara. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-5493-0.

- ^ David Geary; Matthew R. Sayers; Abhishek Singh Amar (2012). Cross-disciplinary Perspectives on a Contested Buddhist Site: Bodh Gaya Jataka. Routledge. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-0-415-68452-1.

- ^ A Dictionary of the Pali Language By Robert Cæsar Childers

- ^ Rupert Gethin (9 October 2008). Sayings of the Buddha: New Translations from the Pali Nikayas. OUP Oxford. pp. xxiv. ISBN 978-0-19-283925-1.

- ^ Beames, John (2012). Comparative Grammar of the Modern Aryan Languages of India: To Wit, Hindi, Panjabi, Sindhi, Gujarati, Marathi, Oriya, and Bangali. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139208871.003. ISBN 978-1-139-20887-1.

- ^ Bechert, Heinz (1995). When Did the Buddha Live?: The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Sri Satguru Publications. p. 129. ISBN 978-81-7030-469-2.

- ^ Sarao, K. T. S. (2003), "The Ācariyaparamparā and Date of the Buddha.", Indian Historical Review, 30 (1–2): 1–12, doi:10.1177/037698360303000201, S2CID 141897826

- ^ Keay, John (2011). India: A History. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0.

- ^ a b Keay, John (2011). India: A History. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0.

- ^ Bechert, Heinz (1995). When Did the Buddha Live?: The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Sri Satguru Publications. ISBN 978-81-7030-469-2.

- ^ a b Geiger, Wilhelm; Bode, Mabel Haynes (25 August 1912). "Mahavamsa : the great chronicle of Ceylon". London : Pub. for the Pali Text Society by Oxford Univ. Pr. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Prasad, Chandra Shekhar (1988). "Nalanda vis-à-vis the Birthplace of Śāriputra". East and West. 38 (1/4): 175–188. JSTOR 29756860.

- ^ Gunapala Piyasena Malalasekera (2007). Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 403–404. ISBN 978-81-208-3022-6.

- ^ Romesh Chunder Dutt (5 November 2013). A History of Civilisation in Ancient India: Based on Sanscrit Literature: Volume I. Routledge. pp. 382–383. ISBN 978-1-136-38189-8.

- ^ Tatz, Mark (1987). "The Life of the Siddha-Philosopher Maitrīgupta". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 107 (4): 695–711. doi:10.2307/603308. JSTOR 603308.

- ^ Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 1056. ISBN 9780691157863.

- ^ Deokar, Lata (2012). "Subhūticandra: A Forgotten Scholar of Magadha". Journal of the Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka. 10: 137–154.

Sources

[edit]- Raychaudhuri, H.C. (1972). Political History of Ancient India. Calcutta: University of Calcutta.

- Law, Bimala Churn (1926). "4. The Magadhas". Ancient Indian Tribes. Lahore: Motilal Banarsidas.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007). Greater Magadha: studies in the culture of early India (PDF). Handbook of oriental studies. Section two, India. Vol. 19. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15719-4. ISSN 0169-9377. OCLC 608455986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2015.

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9