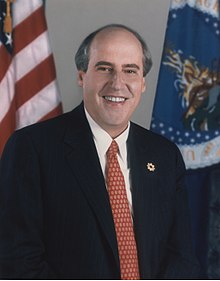

Dan Glickman

Dan Glickman | |

|---|---|

Glickman as the 26th US Secretary of Agriculture, January 1995 – 2001 | |

| Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of the Motion Picture Association of America | |

| In office 2004–2010 | |

| Preceded by | Jack Valenti |

| Succeeded by | Chris Dodd |

| 26th United States Secretary of Agriculture | |

| In office March 30, 1995 – January 20, 2001 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Mike Espy |

| Succeeded by | Ann Veneman |

| Chair of the House Intelligence Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1993 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Dave McCurdy |

| Succeeded by | Larry Combest |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kansas's 4th district | |

| In office January 3, 1977 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Garner E. Shriver |

| Succeeded by | Todd Tiahrt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Daniel Robert Glickman November 24, 1944 Wichita, Kansas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Rhoda Yura (m. 1966) |

| Children | 2, including Jonathan |

| Education | University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (BA) George Washington University (JD) |

Daniel Robert Glickman (born November 24, 1944) is an American politician, lawyer, lobbyist, and nonprofit leader. He served as the United States secretary of agriculture from 1995 until 2001 in the Clinton administration. He previously represented Kansas's 4th congressional district as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives for 18 years.[1]

Following his departure from public office, Glickman led Harvard University's School of Government and Institute of Politics.[1]

He was Chairman and CEO of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) from 2004 to 2010.[2]

He serves as a Senior Fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center, where he focuses on public health, national security, and economic policy issues. He also co-chairs BPC's Democracy Project[3] and co-leads the center's Nutrition and Physical Activity Initiative.

He also serves on the board of directors of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange,[4] MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger,[5] the board of Friends of the World Food Program[6] and is a member of the ReFormers Caucus of Issue One.[7] He also serves on the Council on American Politics at the George Washington University Graduate School of Political Management.[8]

Early life

[edit]Glickman was born in Wichita, Kansas, on November 24, 1944,[1] the son of Gladys A. (née Kopelman) and Milton Glickman.[9] His family was Jewish. The Glickman family operated Glickman Inc., a full-service scrap metal operation, since 1915 and Kansas Metal, an automobile and appliance shredder, since 1994. Glickman Inc. was founded by Jacob Glickman and later continued and expanded by Milton and Bill Glickman. With the death of Milton Glickman, Dan's father, in December 1999, Dan and his siblings Norman and Sharon Glickman carried on the family business until it was sold in 2002.

Glickman graduated from Wichita Southeast High School in 1962.[1] He graduated from University of Michigan with a B.A. in history in 1966,[1] where he was a classmate with one of Al Gore's chiefs of staff, Charles Burson,[10][9] and received his J.D. from The George Washington University Law School in 1969.[1][9] He is married to Rhoda Joyce Yura, with whom he has two children: Jonathan Glickman and Amy Glickman.[9][11]

Legal career

[edit]In 1969 and 1970, Glickman worked as a trial attorney for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, then was a partner in a law firm, Sargent, Klenda and Glickman.[12][11]

Political career

[edit]Wichita Public Schools

[edit]Glickman's first foray into public office was as a publicly elected member of the Wichita School Board, which oversees the Wichita Public Schools (USD-259), one of the nation's largest school districts. Between 1973 and 1976 he served as President of the Wichita School Board.[1][12][11]

U. S. House of Representatives

[edit]Glickman was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives to represent Kansas's 4th congressional district in 1976, serving from January 3, 1977 to January 3, 1995, through eight successive re-elections.[1]

Election

[edit]In 1976, in his first congressional race, Glickman was elected to the House of Representatives as a Democrat from Kansas's 4th congressional district,[1] defeating eight-term Republican incumbent Garner Shriver. Glickman held the office for nine consecutive terms.[1][11][13]

Issues and committees

[edit]Glickman was active in general aviation policy, and co-wrote the General Aviation Revitalization Act (GARA) – controversial landmark legislation providing product liability protection for small airplane manufacturers (his district has produced most of America's light aircraft).[13][11][14][15][16]

During his congressional tenure, Glickman was also active in agriculture issues (his district's other major industry), and served on the House Agriculture Committee, including six years as chair of the subcommittee overseeing federal farm policy. He served as principal author of the 1990 Farm Bill and other legislation. While there, he lobbied for the position of Secretary of Agriculture under President Bill Clinton, losing initially, but winning the post after his tenth-race election ouster from Congress.[9][13][11][17]

In 1986, Glickman was one of the House impeachment managers appointed by the House of Representatives in 1986 to prosecute the case in the impeachment trial of Harry E. Claiborne, judge of the United States District Court for Nevada. Claiborne was found guilty by the United States Senate and removed from his federal judgeship.[1][18]

In 1993, he was appointed chair of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence of the One Hundred Third Congress, serving one term before his 1994 defeat.[1]

In October 1993, Glickman, representing a district whose second-largest industry was agriculture (particularly wheat production), voted for protectionism over free trade, restricting the importation of Canadian wheat.[19]

On "media freedom" versus "family values" one analyst reported that Glickman, in June 1993, voted to require that television shows have explicit viewer advisories.[19] Glickman would later lead the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), which develops such ratings for motion pictures.

In his final term, Glickman was Chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He held open hearings to bring the intelligence community's post–Cold War activities to light and began a committee investigation into the Aldrich Ames espionage case. Colleagues from both parties lauded his quiet, non-grandstanding, "careful and considered" leadership of the committee.[13][9][11]

On abortion, Glickman straddled the fence, generally accommodating abortion, but voting for the Hyde Amendment that restricted federal funding of abortion.[13] In 1993, while on the House Judiciary Committee, he was absent from a key vote on removing most state abortion restrictions, and said later that he was unsure how he would have voted.[20]

Defeat

[edit]In the Republican-landslide 1994 congressional elections, known as the Republican Revolution, Glickman—in his bid for re-election to a 10th term—was unexpectedly defeated by Goddard Republican Todd Tiahrt.[9][21][13][22][23]

Glickman later blamed his surprise defeat largely on his own pro-choice positions, which he said opponents used as an "organizing tool" to rally opposition against him from voters who were otherwise politically inactive.[21][13][22] In a detailed review of Tiahrt's victory, the Chicago Tribune reported that Glickman's unexpected defeat was largely the product of Tiahrt's recruitment of 1,800 volunteers from churches and anti-abortion groups in their congressional district (which had become the center of the national anti-abortion movement[24][25][26][27][28][29]), and from gun-rights organizations.[13]

Another casualty of the 1994 Republican congressional sweep was Glickman's wife, Rhoda, who, for 13 years, had led the Congressional Arts Caucus—one of 28 caucuses soon to be defunded by the incoming Republican Congress.[9]

Post-Glickman era

[edit]As of 2021[update], no other Democrat has won election to the congressional seat lost by Glickman.[23][30]

The court-ordered redistricting in 2012 shifted the Fourth District sharply westward, reaching into more conservative[31] Western Kansas.[32][33]

Secretary of Agriculture

[edit]Following his congressional defeat, Glickman was appointed by President Bill Clinton to be the Secretary of Agriculture, where he served from 1995 to 2001.[1][12]

Glickman had sought the post previously but initially lost his bid to Mississippi Congressman Mike Espy. Glickman's 1994 appointment to the post followed Espy's departure under ethics concerns.[9] Glickman's Senate confirmation was supported by a powerful Republican, Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole, from Glickman's home state of Kansas.

During Glickman's tenure, he participated in implementation of the Department's controversial HACCP Program to control food safety at U.S. food-processing facilities, some of which was subsequently overturned in the federal court Supreme Beef case.[34]

During President Clinton's February 4, 1997 State of the Union address to Congress, Glickman was the "Designated Survivor".[35][36]

When Clinton's term ended, Glickman's career in government ended, but was followed by numerous leadership roles in related institutions and organizations.[13]

Post-government career

[edit]Following his departure from public office, Glickman held a variety of roles in civic-oriented nonprofits.[11] He is a common media interviewee.[37][38][39][34]

Harvard University

[edit]After Clinton's term ended, Glickman became the head of Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government, and later director of Harvard's Institute of Politics.[1][17][13][21]

Aspen Institute

[edit]Glickman became Executive Director of the Aspen Institute Congressional Program, a nongovernmental, nonpartisan discussion fellowship for public leaders.[11]

George Washington University

[edit]Glickman is a Senior Fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and the Council on American Politics at The Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., where he teaches.[11]

University of Southern California

[edit]Glickman is a senior fellow of the Center on Communication Leadership and Policy at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.[11]

Council on Foreign Relations

[edit]Glickman is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, America's pre-eminent foreign policy think tank, led by several former U.S. Secretaries of State and other top former national security leaders.[11]

CIA Advisor

[edit]During President Barack Obama's administration, Glickman served on the External Advisory Board to CIA Director Leon Panetta.[11] (Glickman, while in Congress, had chaired the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.)[1]

Center for U.S. Global Engagement

[edit]Glickman is Chair of the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition, at the Center for U.S. Global Engagement.[11]

Refugees International

[edit]Glickman left the Motion Picture Association of America in 2010 to serve as president of Refugees International. He occupied the post for less than three months.[40]

Food and agriculture

[edit]Glickman's political experience in agriculture led to several post-political roles, including:[11]

- Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy: In 2021, Glickman joined the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University as an adjunct professor of the practice, teaching, mentoring, and contributing to the school's advocacy and public impact.

- Chicago Mercantile Exchange: Glickman serves on the board of directors

- Food Research and Action Center, a domestic anti-hunger organization

- National 4-H Council, board of trustees: The leading national youth agriculture-education program. Glickman favored the expansion of 4-H urban programs[17]

- Meridian Institute: Glickman co-chairs an initiative of eight foundations, administered by the Meridian Institute, to look at long term implications of food and agricultural policy.

- Institute of Medicine: Glickman chairs an initiative at the Institute of Medicine on "accelerating progress on childhood obesity."

- World Food Program-USA: vice-chair

- Chicago Council on Global Affairs: co-chair of its global agricultural development initiative

- Author of "Farm Futures," in Foreign Affairs (May/June 2009)

Issue One – Council for Responsible Social Media

[edit]In October 2022, Glickman joined the Council for Responsible Social Media project launched by Issue One to address the negative mental, civic, and public health impacts of social media in the United States co-chaired by former House Democratic Caucus Leader Dick Gephardt and former Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Kerry Healey.[41][42]

Other roles

[edit]- Communities In Schools, a federation of independent 501(c)(3) organizations in 27 states and the District of Columbia that work to address the "dropout epidemic"—one of the largest dropout-prevention organizations in the U.S., and one of the largest promoters of community-based, integrated student-support services. CIS identifies and mobilizes existing community resources, and fosters cooperative partnerships, such as: mentoring, tutoring, health care, summer and after-school programs, family counseling, and service learning.[11][43]

- William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan, a not-for-profit, independent, research and educational institute dedicated to creating, aggregating, and disseminating intellectual capital on business and policy issues in emerging markets. It provides a forum for business leaders and public policy makers to discuss issues affecting the environment in which these companies operate.[11]

- Advisory Board member for The Michigan in Washington Program at the University of Michigan. The MIW program offers an opportunity each year for 45–50 undergraduates from any major to spend a semester (Fall or Winter) in Washington D.C. Students combine coursework with an internship that reflects their particular area of interest (such as American politics, international studies, history, the arts, public health, economics, the media, the environment, science and technology). The semester in Washington is rigorous. Students work during the day, attend classes in the evenings, and explore the city on weekends.

Motion picture industry

[edit]In 2004, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) announced that Glickman would replace Jack Valenti as its chief lobbyist.[44] Glickman served as Chairman and CEO of the MPAA from 2004 to 2012.[11][45]

When Glickman was named to the MPAA post, his son Jonathan Glickman was serving as President of Spyglass Entertainment Spyglass Media Group and produced such films as While You Were Sleeping and Rush Hour.[46]

A hallmark of Glickman's MPAA tenure was his "war on movie piracy", or the illegal copying and distribution of motion pictures.[17]

In an MPAA press release, May 31, 2006, entitled "Swedish Authorities Sink Pirate Bay", Dan Glickman stated

The actions today taken in Sweden serve as a reminder to pirates all over the world that there are no safe harbours for Internet copyright thieves[47]

In the 2007 documentary Good Copy Bad Copy, Glickman was interviewed in connection with the 2006 raid on The Pirate Bay by the Swedish police, conceding that piracy will never be stopped, but stating that they will try to make it as difficult and tedious as possible.[48]

On January 22, 2010, Glickman announced he would step down as head of the MPAA on April 1, 2010.[49]

Glickman remains, however, a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which dispenses the Motion Picture Academy Awards (Oscars),[11] and the American Film Institute.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "GLICKMAN, Daniel Robert (1944–)", Biographical Information, Bioguide, U.S. Congress official website, retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Cohen, Alex, "Dan Glickman leaves the MPAA," Archived June 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine KPCC, Southern California Public Radio, March 30, 2010

- ^ Dan Glickman Joins the Bipartisan Policy Center Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Bipartisanpolicy.org. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ^ Board of Directors, Chicago Mercantile Exchange Archived April 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Board of Directors, MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger Archived September 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Mazon.org. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ^ Home | Friends of the World Food Program Archived August 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Friendsofwfp.org. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ^ "Issue One – ReFormers Caucus". September 16, 2023.

- ^ "About | The Council on American Politics". GW's Graduate School of Political Management. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jehl, Douglas, "Man in the News – Turning Loss Into Victory – Daniel Robert Glickman," December 28, 1994, New York Times, retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ salon.com, "People" Archived October 27, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. Salon.com (November 3, 1999). Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Dan Glickman," Archived November 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Graduate School of Political Management, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ a b c "Dan Glickman: Agriculture Secretary". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McNulty, Timothy J., "Incumbent's Defeat Is A Case Study In Grass-roots Politics," November 20, 1994, Chicago Tribune, retrieved February 10, 2017

- ^ Kovarik, Kerry V., "A Good Idea Stretched Too Far: Amending the General Aviation Revitalization Act to Mitigate Unintended Inequities," Seattle University Law Review, Vol. 31, No. 4 (2008), Jan.2008, p.973, Seattle Univ. School of Law, Seattle, WA, USA PDF download.

- ^ Rodengen, Jeffrey L., ed. by Elizabeth Fernandez & Alex Lieber, book: The Legend of Cessna (a detailed, documented history of Cessna Aircraft Company, supported by them; most references to this source are coupled with references to more independent sources), Write Stuff Enterprises, 2007, Ft.Lauderdale, Florida. Ch.15–16.

- ^ Bruner, Borgna, ed., table:"Composition of Congress by Political Party, 1855–2005, pp.79–80 in Time Almanac 2006,, Information Please (Pearson), Boston, Mass./ Time Inc., Des Moines, Iowa

- ^ a b c d e "Dan Glickman, The Real Oliver Wendell Douglas," July 3, 2008. CBS News, retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ "List of Individuals Impeached by the House of Representatives". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "Dan Glickman on the Issues,", OnTheIssues.org, retrieved February 16, 2017

- ^ "Divided House Panel Advances Bill To Ease State Abortion Restrictions," May 20, 1993, New York Times, retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ a b c Christopher J. Catizone, "Debate Addresses Abortion Politics," March 9, 2004, Harvard Crimson, retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Hegeman, Roxanna, Associated Press, "Kansas House race divides anti-abortion community," July 20, 2014, Associated Press, in Washington Times, retrieved February 10, 2017

- ^ a b Wingerter, Justin, "Wichita attorney Dan Giroux announces challenge to Rep. Mike Pompeo," October 1, 2015 (Updated October 2, 2015), Topeka Capital-Journal, retrieved February 16, 2017

- ^ "Drive Against Abortion Finds a Symbol: Wichita," August 4, 1991, The New York Times

- ^ Abcarian, Robin, "Abortion doc's killer convicted," January 30, 2010, Chicago Tribune, (originally published January 29, 2010 in Los Angeles Times as "Scott Roeder convicted of murdering abortion doctor George Tiller,"), retrieved February 16, 2017; which says "...Wichita, which became a center of the anti-abortion movement in the late 1980s and 1990s."

- ^ Welch, William M., "Abortion provider was accustomed to threats," May 31, 2009, USA Today, retrieved February 16, 2017; which says: "His practice made him a focal point in the political struggle over abortion, and his hometown became ground zero for anti-abortion activists. In 1993, Tiller was shot in both arms.... His clinic was bombed in 1985...."

- ^ Ball, Karen (Kansas City) "George Tiller's Murder: How Will It Impact the Abortion Fight?," May 31, 2009, Time magazine, retrieved February 16, 2017; which says: "George Tiller long ago erased the line between his private life and his public cause, turning his Wichita, Kans., clinic into ground zero in the fight over late-term abortions.... shot in both arms in 1993 by an antiabortion activist."

- ^ Eligon, John, "Four Years Later, Slain Abortion Doctor's Aide Steps Into the Void: Kansas Abortion Practice Set to Replace Tiller Clinic," January 25, 2013, New York Times, retrieved February 16, 2017; which says: "The [Wichita abortion] clinic was also the focal point of the "Summer of Mercy" protests in 1991... tens of thousands of abortion protesters... more than 2,000... arrested — in an event that transformed... into a national brawl."

- ^ Carmon, Irin "Kansas abortion clinic is back: Three years after George Tiller's murder by an anti-abortionist, his aide is picking up where her mentor left off," September 28, 2012, Salon, retrieved February 16, 2017; which says: "...Wichita, which has been ground zero for the abortion battle since the 1991 Summer of Mercy, when the antiabortion group Operation Rescue set up camp there."

- ^ "Kansas Democratic Party picks James Thompson as nominee for 4th District race," Archived February 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine February 11, 2017, KWCH-TV News, retrieved February 12, 2017

- ^ "Political Geography: Kansas," March 9, 2012, in Five Thirty-Eight blog of the New York Times, retrieved February 12, 2017

- ^ "Court releases redistricting plans; bad news for two conservative Senate hopefuls," June 8, 2012, Wichita Eagle, retrieved February 12, 2017

- ^ "Judges' decision moves Pratt County into 4th Congressional District," June 9, 2012, Pratt Tribune, Pratt, Kansas, retrieved February 12, 2017

- ^ a b "Interviews – Dan Glickman" from episode "Modern Meat," April, 2002, PBS FRONTLINE, Public Broadcasting System (PBS), retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ ["What It's Like Being U. S. Government's Designated Survivor," Part 2 Video], November 23, 2016, ABC 20/20, ABC News, retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ "The truth behind the 'designated survivor,' the president of the post-apocalypse," September 20, 2016, The Washington Post, retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ "TIMES TOPICS: Dan Glickman," New York Times, retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ Search Results for "Dan Glickman", in ABC News (first of multiple pages of listings), retrieved February 10, 2017

- ^ "Search results for Dan Glickman," in National Public Radio (first of multiple pages of listings), retrieved February 10, 2017

- ^ Search Results for "Dan Glickman Refugees International" The Washington Post, retrieved November 4, 2020

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (October 12, 2022). "Facebook whistleblower, former defense and intel officials form group to fix social media". CNBC. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Council for Responsible Social Media – Issue One". issueone.org. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ Jay Mathews, "Dropout-Prevention Program Sees to the Basics of Life," The Washington Post, Dec. 10, 2007; page B01.

- ^ Washington Post, "Glickman Succeeds Valenti At MPAA". The Washington Post. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ^ Motion Picture Association of America Archived February 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Waxman, Sharon (November 11, 2004). "Valenti's Successor, but Not His Clone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "SWEDISH AUTHORITIES SINK PIRATE BAY" (PDF). mpaa.org press_release. May 31, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ Good Copy Bad Copy Archived June 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Good Copy Bad Copy. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ^ The Longest Goodbye in MPAA History. Deadline.com. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

External links

[edit]- 1944 births

- 20th-century Kansas politicians

- American chief executives

- Bipartisan Policy Center

- Chairs of the Motion Picture Association

- Clinton administration cabinet members

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Kansas

- George Washington University Law School alumni

- Harvard University staff

- Jewish American people in Kansas politics

- Jewish members of the United States House of Representatives

- Jewish American members of the Cabinet of the United States

- Living people

- Politicians from Wichita, Kansas

- School board members in Kansas

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission personnel

- Secretaries of agriculture of the United States

- University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts alumni

- Wichita Southeast High School alumni

- Members of Congress who became lobbyists

- Jews from Kansas