Ferdinand Berthoud

Ferdinand Berthoud | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 March 1727 Plancemont-sur-Couvet |

| Died | 20 June 1807 Groslay, Val-d'Oise |

| Occupation(s) | watchmaker, scientist, Horologist-Mechanic by appointment to the King and the Navy |

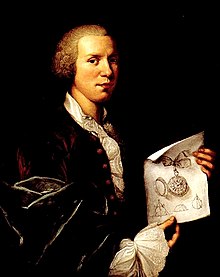

Ferdinand Berthoud (French pronunciation: [fɛʁdinɑ̃ bɛʁtu]; born 18 March 1727, in Plancemont-sur-Couvet, Principality of Neuchâtel; died 20 June 1807, in Groslay, Val d'Oise), was a scientist and watchmaker. He became master watchmaker in Paris in 1753. Berthoud, who held the position of Horologist-Mechanic by appointment to the King and the Navy, left behind him an exceptionally broad body of work, in particular in the field of marine chronometers.

History

[edit]

Ferdinand Berthoud was born on 18 March 1727, in Plancemont, Val-de-Travers, in the Principality of Neuchâtel, which then belonged to the Kingdom of Prussia, into a distinguished family of watch and clock makers.

His father, Jean Berthoud, was a master carpenter and architect. He was a burgher of Couvet, burgher of Neuchâtel, and justice of the peace for Val-de-Travers from 1717 to 1732. His mother, Judith Berthoud (1682–1765) was born in Couvet.

Ferdinand had four brothers: Abraham (1708-?); Jean-Henry (1710–1790), justice of the peace for Val-de-Travers, clerk of the court in Les Verrières, barrister in Cressier, and an expert watchmaker and clockmaker; Jean-Jacques (1711–1784), a draughtsman, and Pierre (1717-?), a farmer and clockmaker. Pierre was a councillor in Couvet, and married Marguerite Borel-Jaquet in 1741. With her, Pierre had two sons, Pierre Louis (born in Paris in 1754, died 1813), and Henri (born ? in Paris, died in 1783); their career was to be closely linked to that of their uncle Ferdinand Berthoud.

Ferdinand also had two sisters: Jeanne-Marie (1711–1804) and Suzanne-Marie (1729-?).

In 1741, when he was fourteen, Ferdinand Berthoud became clockmaking apprentice to his brother Jean-Henry in Couvet, at the same time receiving a sound scientific education. On 13 April 1745, Ferdinand Berthoud finished his training and was awarded a watchmaking and clockmaking apprenticeship certificate.[1][2]

In 1745, aged 18, Ferdinand Berthoud moved to Paris to improve his skills as a watchmaker and clockmaker. He exercised his talents as a journeyman, working with master watchmakers in the Paris community. There is some suggestion in the literature that Ferdinand Berthoud worked for a time for Julien Le Roy, where he is said to have made strikingly swift progress, alongside Pierre Le Roy, his master's son, who later became his rival.[3]

On 4 December 1753, by order of the French Royal Council, in an exception to guild rules and by special favour of the King, Ferdinand Berthoud became a master at the age of 26, receiving the official title of Master Watchmaker.[4][5]

From 1755 onwards, Ferdinand Berthoud was entrusted with the task of writing a number of reference articles on watchmaking for the Encyclopédie méthodique1, published between 1751 and 1772 under the direction of the writer and philosopher Diderot (1713–1784) and the mathematician and philosopher d'Alembert (1717–1783).[6]

Ferdinand Berthoud published his first specialist work in 1759, L'Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres, à l'usage de ceux qui n'ont aucune connaissance d'horlogerie1 [1]. Several other written works followed, detailed in the "Works" section.

In 1763, Ferdinand Berthoud was appointed by the King to inspect the H4 sea watch made by John Harrison (1693–1776) in London, in the company of mathematician Charles-Etienne Camus (1699–1768), a member of the French Royal Academy of Sciences, and astronomer Joseph-Jérôme Lefrancois de La Lande (1732–1807). It was a disappointing trip for Berthoud: Harrison only showed him his H1, H2, and H3 watches (in exchange for a payment of £500), categorically refusing to show him the legendary H4, the most advanced of them all.[7]

Although Berthoud was not able to see Harrison's famous H4 in London, his trip did offer him a way into English scientific circles, due to the importance of his works and publications in the field of watchmaking. This resulted in him being elected on 16 February 1764 as an "associate foreign member" of the Royal Society in London.[8]

In 1764, by order of the King, the French Academy instructed two of its members, Duhamel de Monceau and Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche, to test Ferdinand Berthoud's number 3 sea watch at sea. Berthoud reported that he wore the watch personally in Brest and was present for the tests. The trials took place on the frigate L'Hirondelle.[9]

In 1765, Ferdinand Berthoud undertook a second trip to London to meet Harrison through the offices of Count Heinrich von Brühl (1700–1763), Minister of Saxony. Harrison once again refused to present his creations to Berthoud, knowing that he was fully capable of using them to benefit the French Navy. It was the English horologist Thomas Mudge (1715–1795), famous for his development of the first detached lever escapement and a member of the Board of Longitude, who described the working principle of the H4 watch to Berthoud, without him being able to see it for himself (Harrison demanded a payment of £4,000 for a description of his watch, an exorbitant and dissuasive amount).[10]

On 7 May 1766, Ferdinand Berthoud sent a paper to the Duke of Praslin (1712–1785), Count of Choiseul, Minister of the Navy, explaining his plan to build the Number 6 and Number 8 Sea Clocks. He asked him for an allowance of £3,000 in consideration of his work on earlier sea clocks and in anticipation of his estimated costs for the production of two new sea clocks using English technology. The paper clearly set out Ferdinand Berthoud's ambitions to receive this allowance, together with the title of Horologist-Mechanic by appointment to the King and the Navy, and to devote himself to developing sea clocks and determining longitude at sea. On 24 July 1766, the King approved the project to build the two sea clocks and agreed to finance it.[11]-[12]

To check the performance of the new sea watches, on 3 November 1768, the Duke of Praslin gave Sea Clocks numbers 6 and 8 to Charles-Pierre Claret, the 'Knight of Fleurieu' (1738–1810), explorer, hydrographer, and King's lieutenant, accompanied by Canon Pingré (1711–1796), navy astronomer and geographer and member of France's Royal Academy of Sciences. Their mission was to test the watches on the corvette Isis during a voyage from Rochefort to Santo Domingo and back. The voyage lasted ten months and the trials on the clocks were successful. The findings of Charles-Pierre Claret were published in 1773 under the title Voyage fait par ordre du roi, pour éprouver les horloges marines.[13]

In 1769, Ferdinand Berthoud sent for his nephew Pierre-Louis Berthoud (1754–1813), commonly known as Louis Berthoud, a talented young watchmaker and clockmaker, inviting him to come to Paris from Couvet, Switzerland, to pursue his apprenticeship. Louis helped Ferdinand manufacture and repair the sea clocks his uncle supplied to the French and Spanish navies.

On 1 April 1770, following the successful sea trials of Sea Watches numbers 6 and 8, Ferdinand Berthoud received the title of Horologist-Mechanic by appointment to the King and the Navy, with an annual allowance of £3,000 and responsibility for inspecting the construction of sea clocks. He received a royal commission for 20 sea clocks.[14]

Ferdinand Berthoud's clocks soon became a success and were used on board ship for various test campaigns and charting voyages.

In 1771, Borda boarded the frigate Flore, under Lieutenant Verdun de la Crenne, for a campaign of tests on sea chronometers, sailing from the Canary Islands to the Caribbean. Count Chastenet de Puységur (1752–1809), captain of the corvette Espiègle, accompanied Borda, captain of Boussole, in an expedition to the Canaries and the coast of Africa in 1774 and 1775.[15]

On 1 August 1785, Ferdinand Berthoud gave five clocks to the captain of the Astrolabe, Lapérouse, as he was leaving on an expedition around the world with the aim of adding to the discoveries of James Cook in the Pacific Ocean. The clocks taken on board were lost at sea in the wreck of the Astrolabe in 1788 off the coast of Vanikoro in the Santa Cruz Islands, near the Solomon Islands.

In 1791, Berthoud supplied four marine chronometers to Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux, to aid his expedition to search for Lapérouse with the frigates Recherche and Espérance.[16]

In 17951, Berthoud was elected First Class Resident Member of the Mechanical Arts section of France's National Institute (Institut de France). Following the French Revolution, Berthoud moved in to the Louvre and received an allowance from the State, continuing to work on his clocks and maintain sea clocks. His most important priority, however, was the publication of his most significant work: Histoire de la Mesure du temps2 (1802).[17]

On 17 July 1804, Napoleon made Berthoud a Knight of the Legion of Honour, as a member of the institute.[18]

On 20 June 1807, Ferdinand Berthoud died childless at the age of 80. He was buried in Groslay, in the Montmorency Valley (Val d'Oise), where a monument commemorates him.[19]

Works

[edit]

In 1752 at the age of 25, seven years after he arrived in Paris, Ferdinand Berthoud submitted an equation clock to the Royal Academy of Sciences, thus demonstrating his extraordinary proficiency in the art of watchmaking4]. French Academy members Charles Étienne Camus (1699–1768), a mathematician and astronomer, and Pierre Boger (1698–1758), a mathematician, physicist, and famous hydrographer, wrote a glowing report on the quality of his work.[20]-[21]

Ferdinand Berthoud filed various sealed envelopes with the French Royal Academy of Sciences. On 20 November 1754, he filed the plan for a Machine for measuring time at sea, in a sealed envelope that was never published[5]. This was his first plan for a sea clock. The envelope was not opened until 1976 by the President of the academy.

On 13 December 1760, Ferdinand Berthoud filed his Mémoire sur les principes de construction d'une Horloge de Marine1 with the French Royal Academy of Sciences to present his legendary Sea Clock Number 1, the construction of which was completed in early 1761. He filed an addendum on 28 February 1761. The clock was displayed in April 1763 at the Royal Academy of Sciences.[22]-[23]

In 1754, the French Academy of Sciences approved a watch and equation clock by Ferdinand Berthoud.[24]-[25]

Ferdinand Berthoud devoted himself to research and passing on his knowledge through his publications. This twofold aim earned him rapid acceptance in the scientific circles of his day. Several articles in the Encyclopédie méthodique, published in 1751–1772, under the direction of Diderot (1713–1784) and d'Alembert (1717–1783), were entrusted to him.[26]

In 1759, Berthoud published a successful popular treatise, L'Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres. À l'usage de ceux qui n'ont aucune connaissance d'horlogerie1.6 In 1763, his lengthy treatise L'Essai sur l'horlogerie ; dans lequel on traite de cet Art relativement à l'usage civil, à l'Astronomie et à la Navigation was also well received. This popular work was very successful, translated into several languages, and republished several times in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

1763 marked a turning point in Berthoud's career, which from then on focused on the progress of maritime navigation. Once again, the French Academy of Sciences was to be both a witness and a support: in that year, the watchmaker had two envelopes opened that had been filed in 1760 and 1761. These describe the Sea Clock number 17. On 29 August of the same year, Ferdinand Berthoud filed another envelope entitled Construction d'une montre marine...

His work was characterised by regular projects accompanied by detailed requests. For instance, he proposed the construction of two sea watches on 7 May 1766. These were Numbers 6 and 8, now preserved at the French Museum of Arts and Trades. Following successful experiments with them, Ferdinand Berthoud received the title of "Horologist-Mechanic by appointment to the King and the Navy for the inspection of the construction of sea clocks" on 1 August 1770.[27]

In 1773, Ferdinand Berthoud published his Traité des horloges marines contenant la théorie, la construction, la main-d'œuvre de ces machines et la manière de les éprouver, pour parvenir par leur moyen, à la rectification des cartes marines et à la détermination des longitudes en mer. This treatise was a first, detailing all the parts required for building a sea clock. It helped seal the reputation of Berthoud's work, in particular with respect to his competitors in longitude at sea research, such as Harrison and Pierre Le Roy (1717–1785).

Two years later, in 1775, Ferdinand Berthoud published another work, Les longitudes par la mesure du temps ou méthode pour déterminer les longitudes en mer avec le secours des horloges marines, suivie du recueil des tables nécessaires au pilot pour réduire les observations relatives à la longitude et à la latitude. A second edition of this book was published in 1785.

In 1787, Berthoud published De la Mesure du Temps ou supplément au traité des horloges marines et à l'Essai sur l'horlogerie, contenant les principes d'exécution, de construction et d'épreuves des petites horloges à longitudes et l'application des mêmes principes de construction aux montres de poche, ainsi que plusieurs construction d'horloges astronomiques. This was translated into German in 1798.

In 1792, Ferdinand Berthoud published his Traité des montres à Longitudes contenant la construction, la description & tous les détails de main-d'œuvre de ces Machines ; leurs dimensions, la manière de les éprouver, etc., in which he recommended compensation using the balance wheel, with final adjustment using the spiral (page 172), to achieve better isochronism.

Four years later, in 1796, Berthoud published the Suite du Traité des montres à longitudes, contenant : 1° la construction des montres verticales portatives, 2° la description et les épreuves des petites horloges horizontales plus simples et plus portatives pour servir dans les plus longues traversées.

In 1802, Ferdinand Berthoud published one of his most important works: Histoire de la mesure du temps par les horloges, in which he demonstrates his outstanding knowledge of the art of horological mechanics.

In 1807, the year of his death, Berthoud published his final work, entitled Supplément au Traité des montres à Longitudes avec appendice contenant la notice ou indication des principales recherches ou des travaux faits par Ferdinand Berthoud sur divers parties des machines qui mesurent le temps depuis 1752 à 1807. Fresh editions were published in 1816 and 1838.

As a determined experimenter, a skilled and daring craftsman, and an inventor keen to pass on his knowledge, Ferdinand Berthoud not only made a contribution to the advance of watchmaking but also promoted the use of precision clocks in the sciences of his day, thus contributing to progress in these various disciplines. He is the only watchmaker to have published the findings of all his research in a detailed, methodical manner. Gifted with a genuine spirit of scientific engineering and an extraordinary capacity for work, Ferdinand Berthoud performed more experiments than any other watchmaker of his day.

Ferdinand Berthoud left behind him an extraordinary output in a variety of fields: sea chronometers, watches and decorative clocks, specialist tools, and scientific measurement instruments, as well as publishing scores of written works and specialist dissertations, totalling over 4,000 pages and 120 copperplates.

The titles, privileges, and testimonials of recognition throughout his career, extending from the reign of Louis XV through to the First Empire, as well as the tributes and studies that highlight his critical renown through to the present day, reflect the importance of his place in the long quest for accuracy.

Main clocks

[edit]-

Berthoud marine clock no.2, with motor spring and double pendulum wheel, 1763.

-

Berthoud marine clock no.3 1763.

-

Berthoud chronometer no.24 (1782).

-

Gilt-bronze mantel clock, dial signed Ferdinand Berthoud (Château de Compiègne).

Bibliography:

- L'Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres. A l'usage de ceux qui n'ont aucune connaissance d'horlogerie, 1759;

- Essai sur l'horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l'usage civil, à l'astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l'expérience, 1763 and 1786;

- Traité des horloges marines, contenant la théorie, la construction, la main-d'œuvre de ces machines, et la manière de les éprouver, pour parvenir, par leur moyen, à la rectification des Cartes Marines et à la détermination des Longitudes en Mer, 1773 ( [archive]);

- Eclaircissemens sur l'invention, la théorie, la construction, et les épreuves des nouvelles machines proposées en France, pour la détermination des longitudes en mer par la mesure du temps, 1773;

- Les longitudes par la mesure du temps, ou méthode pour déterminer les longitudes en mer, avec le secours des horloges marines. Suivie du Recueil des Tables nécessaires au Pilote pour réduire les Observations relatives à la Longitude & à la Latitude, 1775.

- De la mesure du temps, ou supplément au traité des horloges marines, et à l'essai sur l'horlogerie ; contenant les principes de construction, d'exécution & d'épreuves des petites Horloges à Longitude. Et l'apparition des mêmes principes de construction, &c. aux Montres de poche, ainsi que plusieurs constructions d'Horloges Astronomiques, &c., 1787(Read online [archive][28])

- Traité des montres à Longitudes contenant la construction, la description & tous les détails de main-d'œuvre de ces Machines ; leurs dimensions, la manière de les éprouver, etc. 1792;

- Suite du Traité des montres à longitudes, contenant : 1° la construction des montres verticales portatives, 2° la description et les épreuves des petites horloges horizontales plus simples et plus portatives pour servir dans les plus longues traversées, 1796;

- Histoire de la mesure du temps par les horloges, 1802 ;

- Supplément au Traité des montres à Longitudes avec appendice contenant la notice ou indication des principales recherches ou des travaux faits par Ferdinand Berthoud sur divers parties des machines qui mesurent le temps depuis 1752 à 1807, 1807.

Exhibition:

An exhibition dedicated to Berthoud, entitled Ferdinand Berthoud horloger du roi1, was held at the International Museum of Horology in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 19849, and at France's National Naval Museum from 17 January 1985 to 17 March 1985.

Ferdinand Berthoud's work is also permanently on display in a large number of museums in various countries worldwide, in particular at France's National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts, the International Museum of Horology in Switzerland, and the British Museum in London.

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]Ferdinand Berthoud is mentioned in the comedy film Les Tontons flingueurs ('Crooks in clover') when Antoine Delafoy's father asks for the hand of Ferdinand's niece. He sees a clock in the living room and exclaims, "Oh! Late eighteenth century, by Ferdinand Berthoud."

References

[edit]- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 20.

- ^ Source for apprenticeship certificate: Favarger, P., "Attestation d'apprentissage de Ferdinand Berthoud"1 in: Musée neuchâtelois2, Neuchâtel, 1908, pp. 100–103.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 20.

- ^ Paris, National archives, E 1290 A, Order of the Royal Council of 4 December 1753.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 304.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 25.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 25.

- ^ Royal Society library archives, Journal Book, vol. 25, p. 3.

- ^ Ferdinand Berthoud, Traité des montres à longitudes, contenant la construction, la description & tous les détails de main-d'œuvre de ces Machines ; leurs dimensions, la manière de les éprouver, etc.1, Paris: Ph.-D. Pierres, 1792.

- ^ Paris, National archives, Marine G 98, Fol. 11

- ^ Paris, National archives, Marine G 3 571, Fol. 273–274

- ^ Paris, National archives, Marine G 97, Fol. 10–13.

- ^ Paris, National archives, Marine G 97, Fol. 11–13.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 313.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, pages 33–37.

- ^ Ferdinand Berthoud, Traité des montres à longitudes, contenant la construction, la description & tous les détails de main-d'œuvre de ces Machines ; leurs dimensions, la manière de les éprouver, etc., Paris: Ph.-D. Pierres, 1792, p. 15.

- ^ Institut de France, archives, registers 2 A1 and 3 A1.

- ^ letter from the curator of the Legion of Honour Museum, Paris.

- ^ Institut de France, archives of the French Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Institut de France, Archives of the French Academy of Sciences, April 1952 session.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 21.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 305.

- ^ Institut de France, Archives of the French Academy of Sciences, Saturday 13 December 1760 session.

- ^ Histoire de l'Académie des Sciences, année 1754, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Gallon, Machines et Inventions (...), 1777, volume 7, pp. 473–476.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 25.

- ^ Collective work, Catherine Cardinal et al., Ferdinand Berthoud 1727–1807 Horloger mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, La Chaux-de-Fonds: International Horology Museum, Institut L'homme et le temps, 1984, page 313.

- ^ "read online". 1787.

Sources

[edit]- F.A.M. Jeanneret and J.-H. Bonhôte, Biographie neuchâteloise, volume 1, Le Locle, Eugène Courvoisier, 1863, p. 32–45.

- Bruno de Dinechin, Duhamel du Monceau. Connaissance et mémoires européennes, 1999 (ISBN 2-919911-11-2)[1]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Patrick Cabanel, "Ferdinand Berthoud", in Patrick Cabanel & André Encrevé (dir.), Dictionnaire biographique des protestants français de 1787 à nos jours, volume 1: A-C, Les Éditions de Paris Max Chaleil, Paris, 2015, p. 268–269 (ISBN 978-2846211901[2])

- Ferdinand Berthoud (1727-1807). Horloger mécanicien du roi et de la marine, International Museum of Horology, La Chaux-de-Fonds; National Navy Museum, Paris, 1984, 343 p.

Related articles

[edit]- ^ Dupont de Dinechin, Bruno (1999). Duhamel du Monceau : un savant exemplaire au siècle des lumières. [Paris]: Connaissance et mémoires européennes. ISBN 2919911112. OCLC 40875867.

- ^ Cabanel, Patrick; Encrevé, André (2014). Dictionnaire biographique des protestants français de 1787 à nos jours. Tome 1, A-C. Paris: Éd. de Paris M. Chaleil. ISBN 9782846211901. OCLC 903336401.

- People from the Principality of Neuchâtel

- 1727 births

- 1807 deaths

- French clockmakers

- French watchmakers (people)

- 18th-century French artisans

- French scientific instrument makers

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Contributors to the Encyclopédie (1751–1772)

- Knights of the Legion of Honour

- People from Val-de-Travers District