Lord Berners

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

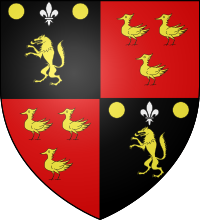

Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, 14th Baron Berners[1] (18 September 1883 – 19 April 1950), also known as Gerald Tyrwhitt, was a British composer, novelist, painter, and aesthete. He was also known as Lord Berners.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Berners was born in Apley Hall, Stockton, Shropshire, in 1883, as Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt,[2] son of The Honorable Hugh Tyrwhitt (1856–1907) and his wife Julia (1861–1931), daughter of William Orme Foster, Apley's owner.[3] His father, a Royal Navy officer,[4] was rarely home. He was raised by a grandmother who was extremely religious[5] and self-righteous, and a mother with little intellect and many prejudices. His mother, who was the daughter of a rich ironmaster, and had a strong interest in fox hunting,[6] ignored his musical interests and instead focused on developing his masculinity, a trait Berners found to be inherently unnatural. Berners later wrote, "My father was worldly, cynical, intolerant of any kind of inferiority, reserved and self-possessed. My mother was unworldly, naïve, impulsive and undecided, and in my father's presence she was always at her worst".[7]

Berners was educated at Cheam School and Eton College, then studied in France and Germany while attempting to pass the entry examination for the Foreign Office. He twice failed the examination but instead served as an honorary attache in Constantinople from 1909 to 1911 and then at Rome until after succeeding to his peerage in 1918.[3]

Adult life

[edit]In 1918, Berners became the 14th holder of the Berners Barony, after inheriting the title, property, and money from an uncle.[8][9] His inheritance included Faringdon House, in Faringdon, Oxfordshire, which he initially gave to his mother and her second husband; on their deaths in 1931 he moved into the house himself.[10] In 1932, Berners fell in love with Robert Heber-Percy, 28 years his junior, who became his companion and moved into Faringdon House.[11] Unexpectedly, Heber-Percy married a 21-year-old woman, Jennifer Fry, who had a baby nine months later. For a short time, she and the baby lived at Faringdon House with Heber-Percy and Berners.[12]

As well as being a talented musician, Berners was a skilled artist and writer. He appears in many books and biographies of the period, notably portrayed as Lord Merlin in Nancy Mitford's The Pursuit of Love.[13] He was a friend of the Mitford family and close to Diana Guinness, although Berners was politically apathetic and was deeply dismayed by the outbreak of the Second World War.[14]

Berners was notorious for his eccentricity,[15] dyeing pigeons at his house in Faringdon in vibrant colours and at one point entertaining Penelope Betjeman's horse Moti to tea.[8] The interior of the house was enlivened with joke books and notices, such as "Mangling Done Here". Patrick Leigh Fermor, who stayed as a guest, recalled:

"No dogs admitted" at the top of the stairs and "Prepare to meet thy God" painted inside a wardrobe. When people complimented him on his delicious peaches he would say "Yes, they are ham-fed". And he used to put Woolworth pearl necklaces round his dogs' necks [Berners had a dalmatian, Heber-Percy the retriever, Pansy Lamb] and when a guest, rather perturbed, ran up saying "Fido has lost his necklace", G said, "Oh dear, I'll have to get another out of the safe."[15]

Other visitors to Faringdon included Igor Stravinsky, Salvador Dalí, H. G. Wells, and Tom Driberg.[16]

His Rolls-Royce automobile contained a small clavichord keyboard which could be stored beneath the front seat. Near his house he had a 100-foot viewing tower, Faringdon Folly, constructed as a birthday present in 1935 for Heber-Percy,[16] a notice at the entrance reading: "Members of the Public committing suicide from this tower do so at their own risk".[17] Berners also drove around his estate wearing a pig's-head mask to frighten the locals.[5][13]

He was subject throughout his life to periods of depression which became more pronounced during the Second World War, when he had a nervous breakdown. He lived in lodgings for a period in Oxford where his friend Maurice Bowra got him a job cataloguing books. Following the production of his last ballet Les Sirènes (1946) he lost his eyesight.[14]

Death and epitaph

[edit]He died in 1950 aged 66 at Faringdon House, bequeathing his estate to Robert Heber-Percy,[8] who lived there until his own death in 1987.[18] His ashes are buried in the lawn near the house.[19]

Berners wrote his own epitaph, which appears on his gravestone:

- Here lies Lord Berners

- One of the learners

- His great love of learning

- May earn him a burning

- But, Praise the Lord!

- He seldom was bored.

Music

[edit]Berners' early music, written during his period at the British embassy in Rome during World War I, was avant-garde in style. These are mostly songs (in English, French and German) and piano pieces, many written using his original name, Gerald Tyrwhitt. Later pieces were composed in a more accessible style, such as the Trois morceaux, Fantaisie espagnole (1919), Fugue in C minor (1924), and several ballets, including The Triumph of Neptune (1926) (based on a story by Sacheverell Sitwell) and Luna Park, commissioned for a C. B. Cochran London revue in 1930.[20] His final three ballets, A Wedding Bouquet, Cupid and Psyche and Les Sirènes, were all written in collaboration with his friends Frederick Ashton (as choreographer) and Constant Lambert (as music director).[21]

Berners was also friendly with William Walton. Walton dedicated Belshazzar's Feast to Berners, and Lambert arranged a Caprice péruvien for orchestra, from Lord Berners' opera Le carrosse du St Sacrement. There are also scores for two films: The Halfway House (1943) and Nicholas Nickleby (1947), for which Ealing's music director, Ernest Irving, provided the orchestrations.[21]

Berners himself once said that he would have been a better composer if he had accepted fewer lunch invitations. However, English composer Gavin Bryars, quoted in Peter Dickinson's biography of Berners, disagrees saying: "If he had spent more time on his music he could have become a duller composer".[5] Dinah Birch, reviewing The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me, a biography of Berners written by Robert's granddaughter, Sofka Zinovieff, concurs saying: "Had he committed himself to composition as his life's work, perhaps his legacy would have been more substantial. But his music might have been less innovative, for its amateur quality — 'amateur in the best sense', as Stravinsky insisted — is inseparable from its distinctive flair".[13]

Berners was the subject of BBC Radio 3's Composer of the Week programmes in December 2014.[22]

Literature

[edit]Berners wrote four autobiographical works and some novels, mostly of a humorous nature. All were published and some went into translations. His autobiographies First Childhood (1934), A Distant Prospect (1945), The Château de Résenlieu (published posthumously)[23] and Dresden are both witty and affectionate.[according to whom?]

Berners obtained some notoriety for his roman à clef The Girls of Radcliff Hall (punning on the name of the famous lesbian writer), initially published privately under the pseudonym "Adela Quebec",[24] in which he depicts himself and his circle of friends, such as Cecil Beaton and Oliver Messel, as members of a girls' school. This frivolous satire, which was privately published and distributed, had a modish success in the 1930s. The original edition is rare; rumour has it that Beaton was responsible for gathering most of the already scarce copies of the book and destroying them.[25] However, the book was reprinted in 2000 with the help of Dorothy Lygon.[26]

His other novels, including Romance of a Nose, Count Omega and The Camel are a mixture of whimsy and gentle satire.

Bibliography

[edit]

Fiction

[edit]- 1936 – The Camel

- 1937 – The Girls of Radcliff Hall

- 1941 – Far From the Madding War

- 1941 – Count Omega

- 1941 – Percy Wallingford and Mr. Pidger

- 1941 – The Romance of a Nose

[See Collected Tales and Fantasies, New York, 1999]

Non-fiction

[edit]- 1934 – First Childhood

- 1945 – A Distant Prospect

- 2000 - The Chateau de Resenlieu

- 2008 - Dresden

Legacy

[edit]In January 2016, he was played by actor Christopher Godwin in episode 3 of the BBC Radio 4 drama What England Owes.[27]

See also

[edit]- Lord Berners profiled in Loved Ones, a book of pen portraits by close friend Diana Mitford.

Sources

[edit]- Amory, Mark (3 June 1999). Lord Berners: The Last Eccentric (New ed.). Pimlico. ISBN 978-0712665780.

- Berners, Lord Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson (1942). First Childhood. Constable & Co Ltd. ASIN B002S9ZE5C.

- Dickinson, Peter (18 September 2008). Lord Berners: Composer, Writer, Painter (Annotated ed.). Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843833925.

- Jones, Bryony (2 January 2003). The Music of Lord Berners (1883–1950): The Versatile Peer (Illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0754608523.

- Lyon Clark, Beverly (11 January 2001). Regendering the school story: Sassy sissies and tattling tomboys. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415928915.

- Tamagne, Florence (1 November 2005). History of Homosexuality in Europe Between the Wars, Vol. I & II Combined. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0875863566.

- Zinovieff, Sofka (16 October 2014). The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother And Me. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0224096591.

References

[edit]- ^ Gerald Tyrwhitt-Wilson at the National Portrait Gallery

- ^ The surname became Tyrwhitt-Wilson by royal licence in 1919, after he had acceded to the Berners barony and baronetcy (Amory, ch. VI)

- ^ a b The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 59. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 540. ISBN 0-19-861409-8.Article by Mark Amory, who wrongly titles Foster as 'Sir' though he was neither knighted nor a baronet.

- ^ Jones (2003), p. 1.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Damian (20 September 2008). "Review: Lord Berners by Peter Dickinson". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Furbank, P.N. (21 May 1998). "Lord Fitzcricket". London Review of Books. 20 (10). London: 32. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Berners (1942), Chapter 'My Parents'.

- ^ a b c Cecil, Mirabel (18 October 2014). "My mad gay grandfather and me". The Spectator. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Jones (2003), p. 2.

- ^ Seymour, Miranda (24 April 2015). "'The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me', by Sofka Zinovieff". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Cecil, Mirabel (18 October 2014). "My mad gay grandfather and me". The Spectator. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Cooke, Rachel (19 October 2014). "The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me review – a family saga with all the trimmings". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Birch, Dinah (11 October 2014). "Composer, novelist, poet, painter and hedonistic host – the real Lord Merlin and his glamorous, desperate world". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 59. p. 542.

- ^ a b Amory (1999).

- ^ a b Cooke, Rachel (19 October 2014). "The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me review – a family saga with all the trimmings". The Observer. London. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Wilkes, Roger. "Cultured country house". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Zinovieff (2014).

- ^ "Oops – we can't find that page".

- ^ Luna Park, Chester Music

- ^ a b Lane, Philip. Notes to Naxos CD 8.555223 Archived 4 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine (2021)

- ^ "Radio 3 Composer of the Week". BBC Online. 5 December 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Jones (2003), p. 3.

- ^ Amory 1999; Jones 2003, pp. 9, 101, 143; Lyon Clark 2001, p. 143.

- ^ Tamagne (2005), p. 124.

- ^ "Lady Dorothy Heber Percy". 17 November 2001. Retrieved 24 September 2017 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Radio 4 Afternoon Drama: What England Owes". BBC Online. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

External links

[edit]- Works by Lord Berners at Faded Page (Canada)

- Oxfordshire Blue Plaque to Lord Berners erected on Faringdon Folly on 6 April 2013.

- Portrait of Lord Beners painted by Spanish painter Gregorio Prieto.

- 1883 births

- 1950 deaths

- 19th-century English LGBTQ people

- 20th-century British classical composers

- 20th-century British male musicians

- 20th-century English composers

- 20th-century English LGBTQ people

- 20th-century English male writers

- 20th-century English nobility

- 20th-century English novelists

- Barons Berners

- British ballet composers

- British male opera composers

- Composers for piano

- English autobiographers

- English classical composers

- English film score composers

- English gay politicians

- English gay writers

- English LGBTQ composers

- English LGBTQ novelists

- English male classical composers

- English male film score composers

- English male non-fiction writers

- English male novelists

- English opera composers

- Gay composers

- Gay novelists

- LGBTQ classical composers

- LGBTQ classical musicians

- LGBTQ film score composers

- LGBTQ peers

- Literary peers

- Musicians who were peers

- People educated at Eton College

- People from Faringdon